Even though it may not seem like boxers train their legs due to how skinny they are, you better believe leg workouts are vitally important for boxing. The legs need more than just endurance. They are important for bouncing around the ring and for producing force that can be transferred to the hands when punching.

The boxing leg workout presented in this article will give you knockout power and the feeling of being light on your feet.

Do Boxers Train Legs?

Boxers do train their legs. The boxers that don’t train their legs are missing out on key physical development that can enhance their boxing performance. More experienced boxers and those who are labeled as knockout artists use their legs more when punching compared to less experienced boxers and those that are labeled speedsters or players [1].

Meaning punching harder is highly attributable to the contributions from the legs. Therefore, you should be training your legs as a boxer.

Does Boxing Bulk Your Legs?

Boxing itself does not bulk your legs. That is why the majority of boxers have skinny legs. To build leg muscle, you need to maximize mechanical tension and metabolic stress [2]. Mechanical tension is about high levels of force generation with a muscle stretching and contracting. For example, lifting heavy weights through a full range of motion.

Think about a heavy squat that puts the quadriceps and glutes in a stretched position at the bottom of the squat and shortened position at the top. Metabolic stress on the other hand is simply the build-up of nasty by-products within the muscle caused by energy production [3].

That burning feeling you get during your last few reps of that squat set is the build-up of these by-products and therefore, metabolic stress. But those last few reps also maximize mechanical tension as movement speed slows down allowing for greater cross-bridge connections within the muscle fiber and therefore, greater tension.

This is also why lighter weights closer to failure or failure can result in similar muscle growth to heavier loads [4]. Boxing does not satisfy any of these requirements for muscle growth of the legs. While you may bob and bend your legs while punching, there is not enough force generation, range of motion, or volume to spur muscle growth in the legs.

How To Strengthen Your Legs For Punching?

Strength training for boxing is not just about endless push-ups and sit-ups. It's about developing full-body strength and power. Not necessarily muscle mass. You don’t need big legs to punch hard and having big legs is likely to hamper your boxing conditioning.

Further, since boxing is a weight class sport, having extra muscle mass on the legs unnecessarily adds body mass making it harder to stay in your weight class. Having strong legs is going to help your punching force but your ability to produce force quickly is even more important.

Therefore, traditional strength exercises can have diminishing returns at some point. You need high-velocity strength exercises to train the ability to express this strength within split seconds. Here is a list of exercises to strengthen your legs for punching:

Squats

When you think of training the legs for boxing, I’m sure the squat is the first exercise that comes to mind. Even Canelo seems to enjoy a heavy squat session.

Whether you perform back squats or front squats is up to you and what you feel most comfortable with. Just be aware that front squats will limit the loads you can use as it is limited by the strength of your back.

This means back squats will provide a better maximal strength stimulus for your legs. That doesn't mean you can't get damn strong legs by front squatting, however. And the added back strength is a bonus.

Deadlifts

If you are choosing between the squat and the deadlift, I would pick the deadlift when it comes to leg training for boxing. However, the deadlift can be a viable alternative if you don’t enjoy the squat or you can’t perform the squat for whatever reason.

The trap bar is better than the barbell when deadlifting for boxing. It allows you to lift heavier loads and places less stress on your lower back [5,6]. Sounds like a win-win to me.

Leg Press

Oh no! A machine?! Force generation does not distinguish between exercises. If you feel more comfortable on the leg press than under heavy squats or you have an injury that prevents you from squatting heavy, the leg press is a viable alternative.

You are NOT a strength athlete. Your sport and number one priority is boxing. Strength training is simply a means to improve your boxing performance. Select your exercises appropriately. Not through dogma about machines being “not functional.”

Split Squats

Single leg training doesn't always have to be part of your boxing training but it is good to use these exercises now and then to address any potential muscle imbalances. Split squats can be done on the floor, or as a Bulgarian split squat with the rear leg elevated on a bench.

For more variation, you can perform lunge variations such as forward, lateral, and reverse lunges. All of these are viable options for single-leg training. Just be aware you will not be able to load these as heavy hence why squats, deadlifts, and leg presses are better options for pure strength development.

Jump Squats

The jump squat is the king of lower body power development. It can be loaded lightly or heavily to target different parts of the force-velocity curve. For example, optimal power load (load that maximizes power output) sits between 20-45% of back squat 1RM [7]. The heavier end of the range will target force adaptations while the lower end will target velocity adaptations.

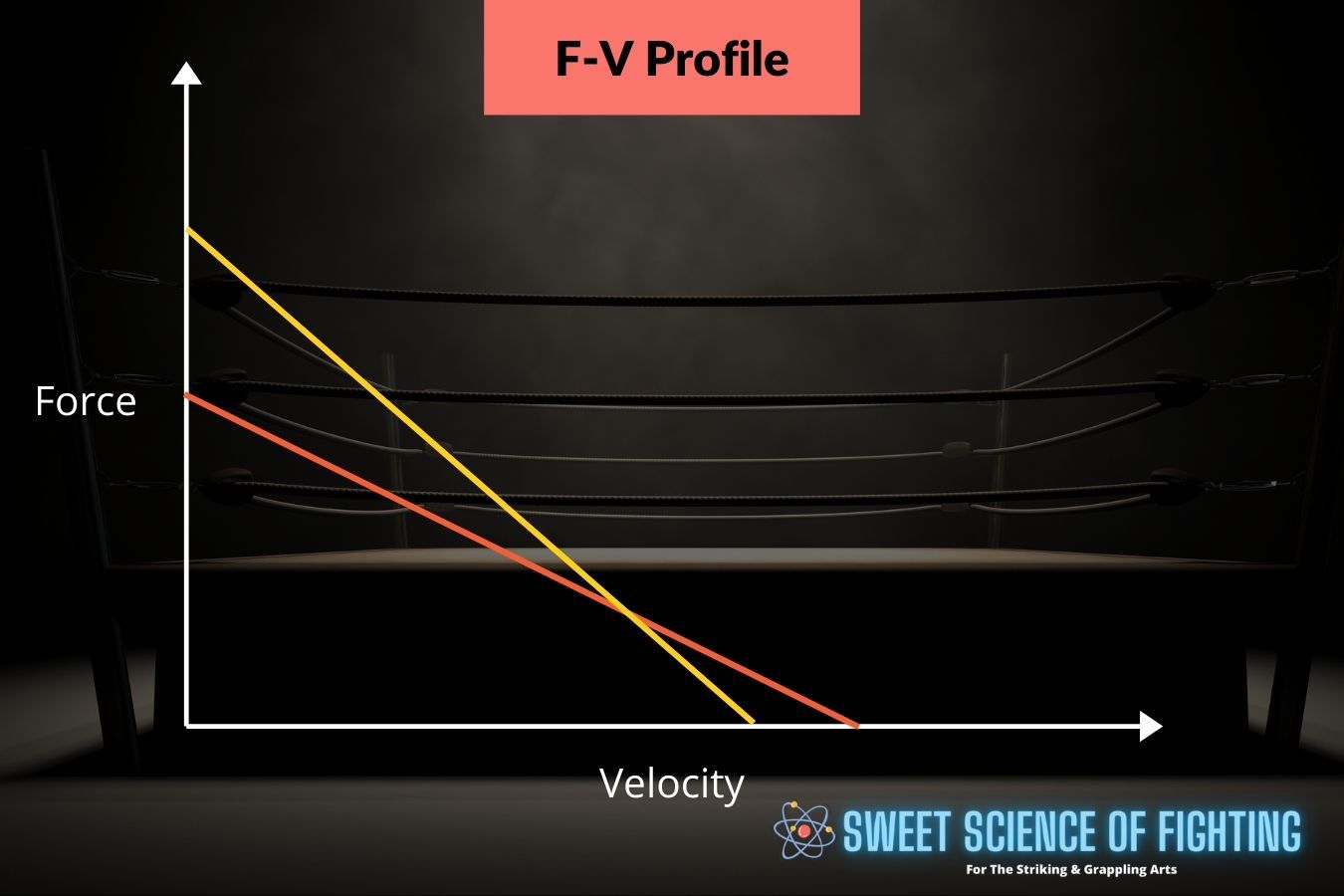

Taking the picture below, the red line indicates an example force-velocity profile of a hypothetical fighter. The yellow line indicates his optimal profile to maximize power output.

This can easily be calculated with an app called My Jump 2 and I run through this extensively in my Warrior Strength Course. In this example, the fighter is deficient in force as the red line is below the yellow line on the y axis. Therefore, he would select heavier loads when jump squatting to maximize power development.

Trap Bar Jumps

If you don’t like jumping with a bar on your back, you can use the trap bar. The great thing about the trap bar is you can easily perform with squat jumps (no countermovement) or countermovement jumps. The countermovement jump involves picking up the trap bar first, then dipping and jumping rapidly.

This replicates the barbell jump squat and trains the stretch-shortening cycle so you can use elastic energy to enhance force production. The trap bar squat jump from the floor removes this elastic energy so it is purely muscular and what would be considered starting strength.

There is no right or wrong here. You can use both variations depending on what you want to target. An easy way to decide is to perform a bodyweight squat jump (no countermovement) and a countermovement jump.

Take both jump heights, and if there is a greater than 10% difference, go with the trap bar squat jump. If there is less than a 10% difference, go with the trap bar countermovement jump.

Box Jumps

The box jump is a staple lower body power exercise. The advantage of a box jump over a vertical jump is the reduced impact at landing since you are jumping onto a box and the added challenge of having a set height to jump in front of you.

It’s important when performing the box jump to not jump off the box. Step down after each jump. Otherwise, you defeat the purpose of the box jump by adding the impact.

Hurdle Hops

The continuous hurdle hop is the fast stretch-shortening cycle exercise making it much different from the various jumps listed above. Jumps are considered a slow stretch-shortening cycle due to the longer time spent on the ground. Hurdle hops are like jumping rope except you’ll be jumping much higher.

This develops leg stiffness so you can produce force quickly as you can use more elastic energy since less energy is dissipated as heat.

Explosive Leg Workout For Boxing

When planning your explosive leg workout, there are a couple of ways to go about it. You can even split these into two distinct phases as your progress. The first one is ordering your leg workout from fast movements to slow movements.

This ensures you are fresh for the explosive exercises so you can maximize speed and power resulting in greater speed and power gains. The second option is to complex the slow and fast exercises together.

This is known as post-activation potentiation or PAP for short. To explain this simply, it's like going to move that table in your friend's living room. It looks heavy so when you go to lift it, you put as much effort as you can to lift it.

But it’s actually light. So, it flies off the floor quickly to your surprise. The PAP effect has you perform a heavy strength exercise like the squat. After that, you go to perform an explosive exercise like a box jump. You've neurally imprinted this heavy-lift into your brain so when you go jump, it's like jumping with the force you'd need to perform the heavy squat.

Resulting in being able to jump higher with greater force, velocity, and power. So, this is how each phase could look:

Phase 1: Fast to Slow

A1) Jump Rope 3 x 50-100

B1) Box Jump 3 x 3-5

C1) Trap Bar Jump 3 x 4 @30% of deadlift 1RM

D1) Back Squat 4 x 3 @83% 1RM

Phase 2: Complex Training

A1) Jump Squat 3 x 3 @40% of squat 1RM

A2) Hurdle Hop 3 x 10

B1) Back Squat 4 x 3 @83% 1RM

B2) Box Jump 3 x 3-5

Summary

The above boxing leg workouts are an example of how things can be done. However, you don’t need to split your training into body parts and rarely should. I much prefer a full-body approach especially when you are only strength training 2-3 times per week so you can make the best progress.

References

1. Filimonov VI, K.K., Husyanov ZM, & Nazarov SS., Means of increasing strength of the punch. NSCA Journal, 1985. 7: p. 65-66.

2. Schoenfeld, B. J. (2010). The mechanisms of muscle hypertrophy and their application to resistance training. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 24(10), 2857-2872.

3. Schoenfeld, B. J. (2013). Potential mechanisms for a role of metabolic stress in hypertrophic adaptations to resistance training. Sports medicine, 43(3), 179-194.

4. Schoenfeld, B. J., Peterson, M. D., Ogborn, D., Contreras, B., & Sonmez, G. T. (2015). Effects of low-vs. high-load resistance training on muscle strength and hypertrophy in well-trained men. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 29(10), 2954-2963.

5. Lockie, R. G., Moreno, M. R., Lazar, A., Risso, F. G., Liu, T. M., Stage, A. A., … & Callaghan, S. J. (2018). The 1 repetition maximum mechanics of a high-handle hexagonal bar deadlift compared with a conventional deadlift as measured by a linear position transducer. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 32(1), 150-161.

6. Swinton, P. A., Stewart, A., Agouris, I., Keogh, J. W., & Lloyd, R. (2011). A biomechanical analysis of straight and hexagonal barbell deadlifts using submaximal loads. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 25(7), 2000-2009.

7. Harris, N. K., Cronin, J. B., Hopkins, W. G., & Hansen, K. T. (2008). Squat jump training at maximal power loads vs. heavy loads: effect on sprint ability. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 22(6), 1742-1749.