Search Tabata workouts, and you’ll be bombarded with a slew of randomly put-together circuits, all with the same 20 seconds on, and 10 seconds off for 4-minute circuits.

Fighters often love Tabata, and you can even find Tabata circuits specifically put together for martial artists. MMA seems to love Tabata. To the uninitiated, this may seem like a great way to prepare for a fight.

However, the Tabata protocol shouldn’t be used by fighters to prepare for a fight due to the huge levels of fatigue associated with the Tabata protocol, potentially negatively affecting your technical training. Further, adaptations cease after approximately 3-4 weeks, leaving you little room for improvement.

Before we dive into more detail on why not to use Tabata and what to do instead, it’s important to understand what the Tabata protocol really is.

What Is Tabata?

The Tabata protocol is one of the most bastardized training protocols within the fitness community. The original Tabata protocol was birthed from a study in 1996 by Japanese researcher Dr. Izumi Tabata [1].

To perform the Tabata protocol as per the study, you would need to spend approximately 4 minutes on the stationary bike, 4 times per week. You would need to perform 20 seconds at 170% VO2max with 10 seconds rest for 7-8 reps.

The 5th day of the week consisted of steady-state cardio for 30 minutes with only 4 non-exhaustive 20/10 second intervals. For reference, cycling at 100% of VO2max would be a pace you could keep for approximately 5-6 minutes. At 170% VO2max, you could hold the pace for about 50 seconds.

For the Tabata protocol to be Tabata, you must be completely exhausted by the 7th or 8th rep, meaning you cannot reach the prescribed intensity. This means that performing a Tabata circuit of push-ups, burpees, and battle ropes are nowhere near intense enough to reach this level of exhaustion.

How to Dominate Every Fight with Raw, Explosive Power No One Can Match

Discover the underground blueprint that has quietly turned MMA hopefuls into legends, using nothing but sheer, brute force and bulletproof conditioning techniques.

In fact, the intensity of Tabata is so brutal that in Dr. Tabata’s follow-up study, only 66% of the subjects maintained the intensity for the last interval [3].

In Dr. Tabata’s latest review study, he mentions that the most important characteristic of the Tabata protocol is cycling to exhaustion [2].

If you can perform more than 7-8 sets before exhaustion, then intensity must be increased. If you can’t reach rep number 7, the intensity must be decreased.

When most fighters are trying to use the Tabata protocol, they are really just performing high-intensity interval training (HIIT), which in this instance is defined as short (<10 seconds) or long (>20-30 seconds) maximal intensity efforts interspersed with recovery periods [4].

A common trend is for fighters to perform “Tabata” sets for more than 4 minutes. Based on what I have described, this is far removed from the Tabata protocol and would be considered HIIT instead, as HIIT can last from 5 minutes to approximately 40 minutes, depending on the interval and recovery length.

If fighters are performing HIIT instead of Tabata, wouldn’t performing the Tabata protocol properly be beneficial for fighters due to the intermittent and intense nature of martial arts?

Why Tabata Is NOT Good For Fighters

This may fly in the face of conventional wisdom. But the Tabata protocol is NOT a good training routine for fighters of all martial arts disciplines. And I am going to list the many reasons why.

Tabata Adaptations Max Out Quickly

Many praise Tabata because of its ability to stimulate improvements in aerobic and anaerobic capacities within a short time frame. However, these adaptations hit the ceiling quickly, and performing more Tabata sessions doesn’t seem to spur any more improvements [1].

While the original Tabata study was performed over 6 weeks, VO2max maxed out at 3 weeks with no significant improvements from weeks 3 to 6. Anaerobic capacity improved until week 4, with no significant changes from week 4 to 6.

Which begs the question, what do you do after week 4 to continue to promote aerobic and anaerobic adaptations? I doubt driving the intensity even higher with an intensity already so high would stimulate greater adaptation.

Furthermore, the subjects in the Tabata study were recreational sporting college students, so it is difficult to extrapolate these fast physiological changes to an athletic population that trains consistently for their competitive martial art.

Tabata Causes High Levels Of Fatigue

With Tabata being performed to exhaustion 4 times a week, there is little room for other forms of training. The most important aspect of martial arts performance is technical and tactical skills. Being fatigued when performing skill work isn’t the best way to plan your training.

Even if you were to reduce the number of Tabata sessions per week in half, two exhausting sessions per week take away from something else- even if they are just 4 minutes in length.

I am not saying that hard, exhausting training sessions shouldn’t be done. Not at all. Especially when higher intensity exercise is needed to stimulate anaerobic capacity adaptations, which have extra importance in martial arts such as wrestling.

Also, the ability of the anaerobic lactic energy system to continually buffer acidic waste products from the working muscles is vitally important.

But there are more effective ways of developing anaerobic capacity for combat sports that don’t require multiple days of exhaustion sitting on a bike.

These could as simple as performing near maximal combinations on the heavy bag or near-maximal double leg shots within the anaerobic capacity training guidelines.

Furthermore, many of these anaerobic capacity-style drills may not even be needed because sparring and more intense training occur as the athlete progresses closer to a fight.

Tabata Is Difficult To Perform With Other Exercise

Tabata is very difficult to perform using other exercises without concrete evidence to suggest otherwise. One study tried to replicate the Tabata protocol using kettlebell (KB) swings [5].

The problem with this study is that the KB Tabata protocol was compared to another KB protocol which consisted of 4 sets with 90 seconds rest with the total number of reps performed during the Tabata split evenly between the 4 sets.

All that study was able to conclude was a 20-second on, 10 seconds off KB swing protocol was more effective than performing 4 sets of the same number of swings. I highly doubt it would’ve shown improvements anywhere near the original Tabata protocol. You just can’t reach that kind of intensity using KB swings.

If combat sports were purely physiology, then performing Tabata intervals close to a fight might be a great idea. However, combat sports aren’t cyclical like running, cycling, or swimming, where a repetitive action is taken throughout the competitive event.

When training for various combat sports, your conditioning time is best spent performing the sport itself. That means manipulating drills to involve fight techniques that fit within the structure of the adaptations you want to stimulate.

If this is targeting the aerobic energy system, it may be performing long-duration shadowboxing or shadow wrestling. For the anaerobic energy system, it may be shorter bursts of near-maximal activity with complete or incomplete rest.

Various technical drills can be used to prepare for specific fight work to rest ratios or push the Worst Case Scenario.

Best Cardio Training For Fighters

When using high-intensity exercise such as Tabata, the primary goal is generally to improve anaerobic energy system properties. Lower-intensity exercise is a much more suitable option if this is not the goal.

The best cardio training for fighters is going to depend on a few different factors:

- The combat sport the fighter is participating in.

- The individual conditioning profile of the fighter.

- How far they are from a fight.

However, some general rules ring true regardless of these factors. A well-developed aerobic energy system through low-intensity, high-volume work lays the foundation for high-intensity exercise to elicit large and fast adaptations [6].

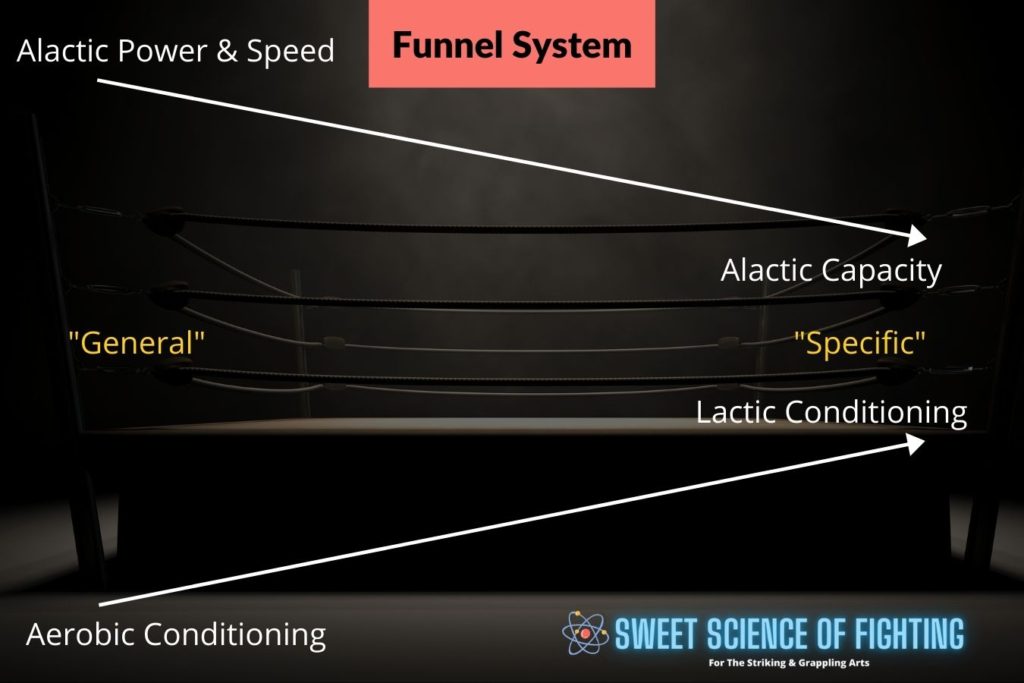

As such, the best approach to take, in my opinion, is using the “Funnel System,” which emphasizes training on the very high (alactic power, speed) and very low (aerobic power and capacity) ends of the conditioning spectrum.

In doing so, you build the gas tank needed for martial arts performance while improving maximum power and speed outputs and the ability to repeat these actions throughout a fight. As you get closer to a fight, conditioning starts to target the anaerobic lactic energy system and the ability to repeat power.

Summary

Tabata sounds great on paper. It’s hard and requires grit like fight does. It takes you to dark places you may experience in the ring, cage, or on the mats. However, there’s little room to move and the fatigue generated from this protocol may reduce the quality of your technical training.

References

1. Tabata, I., Nishimura, K., Kouzaki, M., Hirai, Y., Ogita, F., Miyachi, M., & Yamamoto, K. (1996). Effects of moderate-intensity endurance and high-intensity intermittent training on anaerobic capacity and VO~ 2~ m~ a~ x. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 28, 1327-1330.

2. Tabata, I. (2019). Tabata training: one of the most energetically effective high-intensity intermittent training methods. The Journal of Physiological Sciences, 69(4), 559-572.

3. Tabata, I., Irisawa, K. O. U. I. C. H. I., Kouzaki, M. O. T. O. K. I., Nishimura, K. O. U. J. I., Ogita, F. U. T. O. S. H. I., & Miyachi, M. O. T. O. H. I. K. O. (1997). Metabolic profile of high intensity intermittent exercises. Medicine and science in sports and exercise, 29(3), 390-395.

4. Buchheit, M., & Laursen, P. B. (2013). High-intensity interval training, solutions to the programming puzzle. Sports medicine, 43(10), 927-954.

5. Fortner, H. A., Salgado, J. M., Holmstrup, A. M., & Holmstrup, M. E. (2014). Cardiovascular and metabolic demads of the kettlebell swing using Tabata interval versus a traditional resistance protocol. International journal of exercise science, 7(3), 179.

6. Laursen, P. B. (2010). Training for intense exercise performance: high‐intensity or high‐volume training?. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports, 20, 1-10.