Agility may be the most bastardized components of fitness. Developing strength or cardiovascular fitness can be relatively straight forward as it’s easy to test (but is often still trained improperly). Agility, however, is harder to develop objectively as it is much harder to test.

Improving agility for fighters is by and large achieved through the sport training itself. Agility is improved by developing the decision making factors as well as the physical factors such as technique. No amount of ladder drills will make you more agile.

Before we can train to improve agility within combat sports, we must understand what agility really is. Based on what is seen on TV, Instagram, and YouTube, most coaches and athletes don’t have a firm grasp on agility.

What Is Agility?

I still remember watching an old UFC Countdown where an athlete had an “agility coach.” The “coach” had the fighter catch tennis balls that were being thrown against the wall from behind his back, run through ladder drills, and rapidly switch his hand position from overhand to underhand while holding a barbell. Why is this considered “agility?”

I’m sure you’ve also seen the thousands of Instagram videos of athletes or coaches looking like the video is sped up 2x speed as they do random ladder and cone drills in the sand. What is the point of these obstacle courses?

“Fast feet” is not a good enough explanation.

To fully understand how to train agility for a combat athlete (or any athlete), we must know what agility is. So first, we must define agility for fighters.

Agility for fighters can be defined as the ability to maintain or control body position with a rapid change of velocity or direction in response to a sport-specific stimulus.

How to Dominate Every Fight with Raw, Explosive Power No One Can Match

Discover the underground blueprint that has quietly turned MMA hopefuls into legends, using nothing but sheer, brute force and bulletproof conditioning techniques.

The last part of this definition is the most important so I want you to keep this in mind throughout this article.

Often you’ll hear the term ‘reactive’ agility. However, based on our definition, all agility is reactive as movements are in response to a stimulus. Therefore, the term ‘reactive’ is redundant and will be retired when used in conjunction with agility.

Agility can also be offensive or defensive. For a stand-up fighter or an MMA fighter, offensive agility could be being able to reposition to land a successful counterstrike. For a grappler, it may be reacting to an opponent’s defense to a takedown and quickly switching the technique to complete the takedown.

Defensive agility for a stand-up fighter can be something as simple as slipping a punch while defensive agility for a grappler may be sprawling to defend a double leg. It’s important to note that in combat sports, both fighters are always in a state of attack and defense.

You may notice a theme here. None of these agility maneuvers look anything like catching tennis balls or running through a ladder.

Agility can also be an open and closed skill. What’s the difference? An open agility maneuver means it is in response to the environment (i.e. reactive).

A closed agility maneuver means it is pre-planned. For a stand-up fighter, this may be combinations of the pads. For a grappler, this may be drilling takedowns.

The agility examples I gave at the beginning of this section would all be considered closed chain agility movements. Sadly, these closed chain exercises don’t carry over to competitive fighting. However, that doesn’t mean closed chain agility exercises are useless… Just the ones I mentioned in the beginning are useless.

You will see why shortly.

What Does Research In Fighters & Martial Artists Show?

Do an academic literature search for agility and [insert martial art here] and you’ll find a few journal articles mainly in taekwondo and karate. If you dig deeper into these journals, you’ll see that the tests used to assess agility are closed chain agility running tests or agility tests reacting to a non-sport specific stimulus [1,2].

In fact, some papers just compare athletes of different sports and their reaction times and agility test scores [3,4]. While this may tell us how quickly a fighter moves, it doesn’t tell us anything about how agile they are for their martial art.

To find out why, we need to look outside of the martial arts and into the invasion sports. Invasion sports consist of team sports such as rugby, American Football, soccer, basketball, and hockey to name a few.

But why invasion sports? Because agility to extensively studied in this area as these sports require hundreds of agility maneuvers per match in a multitude of different directions and scenarios.

Breaking Down Agility For Fighters

So let’s breakdown agility for fighters through the research performed in invasion sports. When performing agility tests such as the ones performed in the literature mentioned in the previous section, what is actually being measured is the change of direction speed (CODS).

This means the athlete or fighter knows when, where, and how the COD movement is being performed.

But, CODS and agility are independent qualities. A 2015 study by one of the top experts in agility, Dr. Warren Young, showed that CODS and agility display a correlation of only 21% when averaged out over six different studies on the topic [5].

Since the correlation is well under being 50% related, it indicates CODS and agility are independent of each other. In other words, being quick and changing direction (or quick at bobbing and weaving) does not necessarily mean that you will also be quick when having to react to a sport-specific stimulus such as slipping punches.

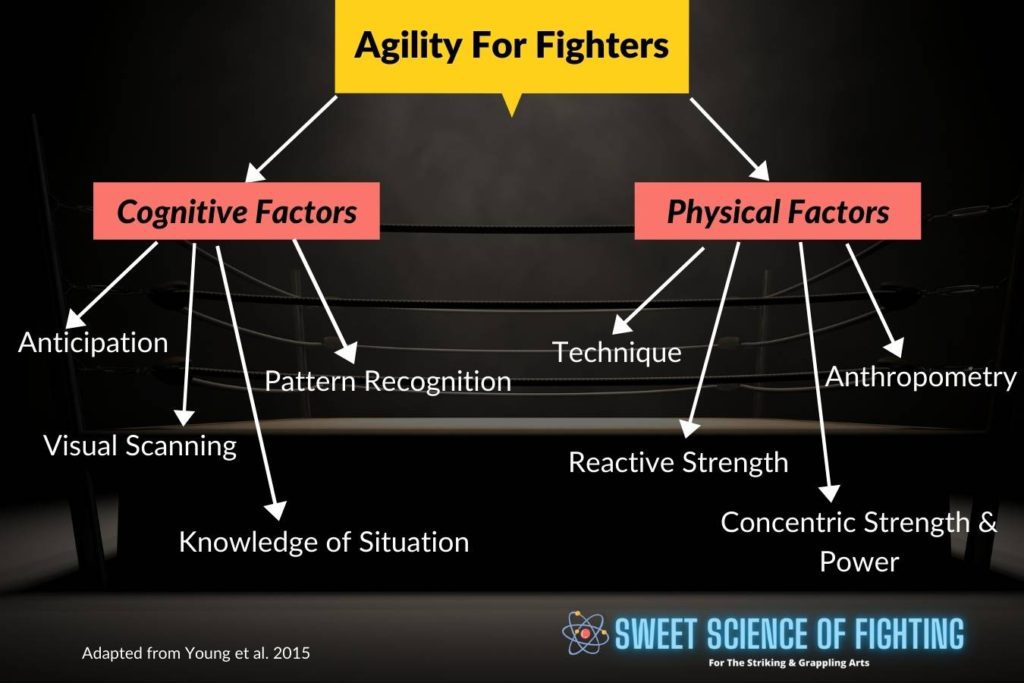

From this, we know that agility is more than just physical. I’ve broken down agility into two main components.

To make this even easier to understand, cognitive ability can be renamed decision making speed and accuracy.

To have great agility, both accurate decision making speed and physical factors must be at a high level. And at a high level for both offensive and defensive agility. This is why you can’t go from only hitting pads with perfect technique and footwork to sparring at a decent level.

There’s an added component that hasn’t been trained when only hitting pads which is the ability to accurately make decisions quickly in response to your opponent’s actions.

In team sports, there is a clear distinction between who is attacking and who is defending.

In combat sports, however, both fighters are attacking and defending at the same time. This means the thought process is slightly different from that of team sports when it comes to agility.

For example, a team sport athlete might be thinking if he can maneuver between defenders but not have to think about defensive maneuvers himself. While a fighter may be thinking if he slips my punch, am I open for a shot?

A more attacking mindset may be throwing feints and seeing how the opponent reacts or pulling on the back of the head to see if they react hard enough to shoot for a takedown.

A defensive thought process may be is his feint setting me up for a head kick or is his wrist control along with his footwork being used to set me up for an arm drag?

Finding the correct solution to an opponent’s movements only comes when a fighter is well experienced and has seen the same or similar scenarios over and over again and has been able to solve the problem.

That is when they can start to anticipate what will happen through their knowledge of the situation by the recognition of similar patterns through visual scanning which allows them to make the correct decision.

How Does Agility Differ Between Elite And Non-Elite Athletes?

One way of deciphering if a quality is important is to compare elite and non-elite athletes. If the higher-skilled athlete performs better in the test, then the quality that that test measures would be deemed important for performance in that sport.

Unfortunately, no research has been performed within combat sports so we will have to turn to team sports again.

In netball and rugby league, higher standard players had faster decision-making times to sport-specific stimuli compared to lower standard players [6,7]. In Australian Rules football, professional players were found to be faster and more accurate in their decision-making ability when reacting to an attacker changing direction compared to elite junior players [8].

Similar results were found in elite soccer players who were faster and more accurate at anticipating pass direction in one on one situations compared to recreational players [9].

Higher skilled athletes are also less susceptible to feints (just watch Adesanya vs. Costa at UFC 253 to see this play out live) [10.11]. But most importantly out of all of this…

Higher skilled athletes ONLY perform better when reacting to a SPORT SPECIFIC STIMULUS.

What does this mean for your training? Performing reaction drills with tennis balls, ladders, or flashing lights provide a stimulus too generic to carry over to fighting. Agility must be trained as an open skill with the sport-specific stimulus with the physical attributes to support it.

How To Train Agility For Fighters

We will break this down into two simple categories from our diagram. Physical and cognitive (decision making) factors.

Physical Factors

Anthropometry

In general, the bigger you are, the slower you move. Especially if you are carrying extra body fat. The goal here is to be as lean as possible to remove excess weight.

Height and limb length is another factor as the taller you are, the more distance you have to cover when evading strikes and defending takedowns. Sadly, there isn’t much that can be done about that.

Reactive Strength

Reactive strength is the ability to produce force in a very limited time window (<250ms). Here is a list of exercises (but not limited to) that can be performed to develop reactive strength:

- Skipping

- Ankle Pops (pogos)

- Hurdle Hops

- Line Jumps

- Drop Jumps

- “Shock” Medicine Ball Chest Throws

Concentric Strength & Power

Concentric strength & power is simply being able to produce force at high speeds in a particular direction. Here is a list of exercises (but not limited to) that can be performed to develop concentric strength & power:

- Box jump

- Seated box jump

- Vertical jump

- Loaded squat jump

- Bench throws

- Medicine ball throws

- Split squat jumps

- Lateral jumps

- Olympic lifts

- Speed squat

- Speed deadlift

- Speed bench press

- Push press

- Power jerk

Technique

This is arguably the most important physical factor for agility in fighters. The technical underpinnings are going to set you up with as many options as possible to choose from when using your agility maneuver.

It’s important to know multiple defensive and offensive agility techniques so you have a repertoire to choose from. If you only know how to slip a punch but don’t know how to angle out or parry a punch or kick, then you only have one option to choose from regardless of the offense being presented to you.

If you only know how to set up a takedown by clinching the back of the head and looking for a reaction, then you won’t recognize other opportunities you may have.

Practicing these techniques can be performed in a closed chain setting where everything is pre-planned. As you become proficient in the movements, they can be assimilated into live or simulated sparring that isn’t at 100%. And that is where the cognitive factors are developed.

Cognitive Factors

Agility isn’t just about making fast decisions. It’s about making fast decisions accurately. You can react as fast as you want but if you choose the wrong technique, you could end up on the floor.

I’m not going to break down each decision making factor separately like I did with physical factors because decision-making factors aren’t performed in isolation. Everything works together through exposure to many different scenarios.

So how do you develop fast, accurate decision-making skills? By being exposed to as many different fight scenarios over and over again. By failing and making the wrong decisions and correcting your technical decision next time you recognize the same pattern or situation. This is how open-chain agility training is performed.

This can’t be developed through pad and bag work. It needs to be learned through light sparring, positional sparring, or hard sparring. For grappling, much of the situational awareness and experience needs to be developed through hard sparring.

You need to be able to put pressure to feel how an opponent will react to what you do. While closed chain drilling may help you recognize the reaction pattern, doing it live is a different story.

Putting An Agility Plan Together For A Fighter

As you may have gleaned from this article, agility can’t be trained through generic stimulus provided by an “agility coach.” Rather agility training predominantly happens within the martial arts training itself.

Here are some guidelines to use for developing agility for fighters.

- Train reactive strength and concentric strength & power 1-2x a week.

- Expand your offensive and defensive technique repertoire in a closed chain environment (pads, partner drills).

- Use live scenarios to see as many different situations as possible and to try and solve the problem with your techniques. Fail and correct.

References

1. Sienkiewicz-Dianzenza, E., & Maszczyk, Ł. (2019). The impact of fatigue on agility and responsiveness in boxing. Biomedical Human Kinetics, 11(1), 131-135.

2. Singh, A., Boyat, A. V., & Sandhu, J. S. (2015). Effect of a 6 week plyometric training program on agility, vertical jump height and peak torque ratio of Indian Taekwondo players. Sport Exerc Med Open J, 1(2), 42-46.

3. Zemková, E., & Hamar, D. (2014). Agility performance in athletes of different sport specializations. Acta Gymnica, 44(3), 133-140.

4. Zemková, E. (2016). Differential contribution of reaction time and movement velocity to the agility performance reflects sport-specific demands. Human movement, 17(2), 94-101.

5. Young, W. B., Dawson, B., & Henry, G. J. (2015). Agility and change-of-direction speed are independent skills: Implications for training for agility in invasion sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 10(1), 159-169.

6. Farrow, D., Young, W., & Bruce, L. (2005). The development of a test of reactive agility for netball: a new methodology. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 8(1), 52-60.

7. Gabbett, T., & Benton, D. (2009). Reactive agility of rugby league players. Journal of science and medicine in sport, 12(1), 212-214.

8. Carlon, T., Young, W., Berry, J., & Burnside, C. (2013). Association between perceptual agility skill and australian football performance. Journal of Australian Strength and Conditioning, 21(1), 42-44.

9. Williams, A. M., & Davids, K. (1998). Visual search strategy, selective attention, and expertise in soccer. Research quarterly for exercise and sport, 69(2), 111-128.

10. Henry, G., Dawson, B., Lay, B., & Young, W. (2012). Effects of a feint on reactive agility performance. Journal of sports sciences, 30(8), 787-795.

11. Jackson, R. C., Warren, S., & Abernethy, B. (2006). Anticipation skill and susceptibility to deceptive movement. Acta psychologica, 123(3), 355-371.